It’s 70 years since Japan surrendered and World War Two ended. But when war with Japan first broke out at the end of 1941 Britain had been woefully unprepared – not least because almost no-one in Britain could speak Japanese.

The only place that taught the language was the School of Oriental and African Studies, now known as SOAS, part of the University of London. So an 18-month course was devised there for bright sixth-formers with a flair for languages.

They were dubbed The Dulwich Boys, and many of them went on to be key players in the post-war relationship between Britain and Japan.

The school’s Japanese-teaching facilities when war broke out were rudimentary.

“Japanese was taught here,” says Prof Ian Brown, who is writing a history of SOAS. “There were two teachers at the end of the 1930s. But classes for Japanese – classes for everything frankly – were rather small.”

The truth was that learning exotic languages was not a priority for imperial Britain in the 1930s. “British investment in Japan was small, and there was no Japanese investment in Britain,” says Sir Hugh Cortazzi, who learned his Japanese at SOAS and became Britain’s ambassador to Tokyo in the 1980s. “And, of course, Japan had been cutting itself off from the West. But I think there was also an element of arrogance on the part of the British.”

The SOAS building in Russell Square, 1943

The shortage of Japanese speakers in 1942 was exacerbated by the disastrous start of Britain’s war with Japan. Within weeks of the surprise attack on the US Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor, which brought the US into the war, the Japanese had launched a successful invasion of Malaya, a British colony, and Britain’s huge military base in Singapore had fallen.

Most of the few who had learnt Japanese at SOAS had, not surprisingly, taken jobs in East Asia. And with the fall of Singapore most had become prisoners of war.

So a desperate War Office decided to advertise scholarships for 18-month intensive courses for sixth-formers in Japanese, Chinese, Turkish and Persian (for who knew where the war might spread to next), to start in May 1942.

One of those who successfully applied was Guy de Moubray, who died in June at the age of 90. He’d been born in Malaya, where his parents were still living, and was at Loretto School near Edinburgh.

“My parents became prisoners of war in February 1942 and it was around then that I put in for this scholarship exam,” he said in an interview recorded by SOAS, “partly because of my parents, but partly because I wanted to get away from school a year earlier than I otherwise would have done.”

De Moubray was one of 30 boys studying Japanese. They were put up at Dulwich College in south London in two of the boarding houses. Each day he and the other “Dulwich Boys” commuted by train to Victoria, and then by bus (if they could afford it) or on foot to SOAS which was based temporarily above St James’s underground station, though it seems to have moved to its present home in Bloomsbury during the Dulwich Boys’ course.

They were a mixed bunch. Sandy Wilson was one, though he soon dropped out – in the 1950s he became famous as the composer of the hit musical, The Boyfriend. “He never took it seriously, he was already writing songs,” remembers a contemporary.

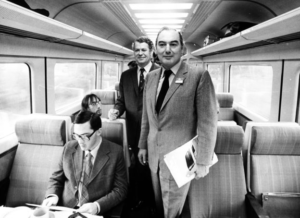

Peter Parker, who later became chairman of British Rail was another – the boys elected him their prefect. Some on the course thought him dynamic, a born leader – others found him hard to take. “Sanctimonious and self-important” was one verdict.

Ronald Dore, another Dulwich Boy, remembers that the group divided naturally into two – the public school types stuck together, and so did the lower middle-class products of grammar schools (of which Dore was one). He thought it a reflection of how class-ridden 1940s Britain was.

Dore, now aged 90, was also one of at least four boys on the language courses who later became professors at SOAS. This sudden influx of bright, highly-motivated and state-funded students provided SOAS with an important shot in the arm which was vital to the school’s post-war expansion.

But in 1942 the biggest problem was a desperate shortage of teachers. Only one of the two pre-war course staff, Saburo Yoshitake, was still in post and he soon left.

“The head of the department and the main teacher was a man called Frank Daniels,” Dore remembers. “He was a clerk in the Admiralty and had been posted to Japan, and there he very assiduously started learning Japanese and acquired a Japanese wife.”

Wartime language students at SOAS – Is the 3rd one Ron ?

Otome Daniels – whom the boys thought very beautiful – also taught on the course. She and her husband had been in Japan when war broke out, but had returned to Britain following a rare prisoner of war swap.

Two second-generation Japanese sergeants in the Canadian army helped out. So did Britain’s former military attache in Tokyo, General Sir Francis Piggott, who one boy remembered “was almost evangelical in teaching us the titles of the whole hierarchy of the Japanese General Staff”.

And there were also instructors with even less orthodox backgrounds. “People who had settled down in Soho as manufacturers of lampshades… and they spoke rather less than high-class Japanese,” Dore says.

And there were a number of Japanese men who had been released from internment. Two of them were correspondents for Japanese newspapers and news agencies.

The shortage of teachers was so acute that Ron Dore, after completing his course, soon found himself back on the staff at SOAS. He had been called up into the army, but injured himself during basic training and was invalided out. Among his pupils was Hugh Cortazzi, then an RAF aircraftsman second class who had signed up for a six-month crash course for servicemen.

There were two service courses. Learning both to speak and read Japanese in such a short time was thought too difficult. So the servicemen trained either as interpreters, who needed to know only the spoken language, or translators, who could read it but not speak it.

In due course the Dulwich Boys themselves were called up. But their first attempts at putting what they had learnt to use weren’t always successful. Guy de Moubray was sent to the frontline in Burma to eavesdrop on Japanese military broadcasts.

“Every time we got to the new front line, one of us had to climb a teak tree to put the aerial up as high as we could,” he recalled, “hoping to receive Japanese regimental radio. Unfortunately, though we tried for over two months, we were never successful.”

The teak forest, he suspects, was just too thick for radio signals to penetrate. Later, he was the first British soldier ashore when Singapore was liberated. There he found his parents, whom he hadn’t seen since he was 14, still alive after three years of Japanese captivity.

The Dulwich Boys’ real impact came after the war. “Without these young men there would be no UK-Japan relationship,” says Dr Christopher Gerteis, the current chair of the Japan research centre at SOAS. “Or if there were it would have rested on the shoulders of an aristocratic class like that of the 1930s. These are the professional statesmen, this is the generation that built the United Nations, that built post-cold war frameworks, that eventually led to the creation of a very strong liberal democracy in post-war Japan.”

Hugh Cortazzi, now aged 91, plays down the impact of the SOAS wartime graduates on Japan’s post-war rebuilding. “The British participation in the occupation was really limited,” he says. “We had no role in respect to military government, that was entirely in the hands of the Americans.”

But his own career is evidence that the Dulwich Boys and their contemporaries at SOAS did become key figures in Anglo-Japanese relations. Some, like Cortazzi, became diplomats. Several, like Ron Dore, became academic experts on Japan. And then there was Sir Peter Parker.

After resigning from British Rail, Parker became a director of Mitsubishi. In the 1980s he chaired an inquiry for the government into the teaching at universities of “difficult” languages – a professorship of Japanese at Cambridge was one indirect result.

The Japanese liked him, according to Cortazzi. “I think they respected Peter. He had great personal charm, he was interested in Japanese culture, he would always be repeating a haiku at every possible occasion. And when we were working for the establishment of a Japan festival in Britain in 1991 we were clear that the only person who could really be chair of it was Peter Parker.”

The irony, perhaps, is that it took a war, and a bunch of clever schoolboys, to bring about such a remarkable improvement in Britain’s understanding of and relations with Japan.

Ron Silk in memory